Interview Urban

Horizont

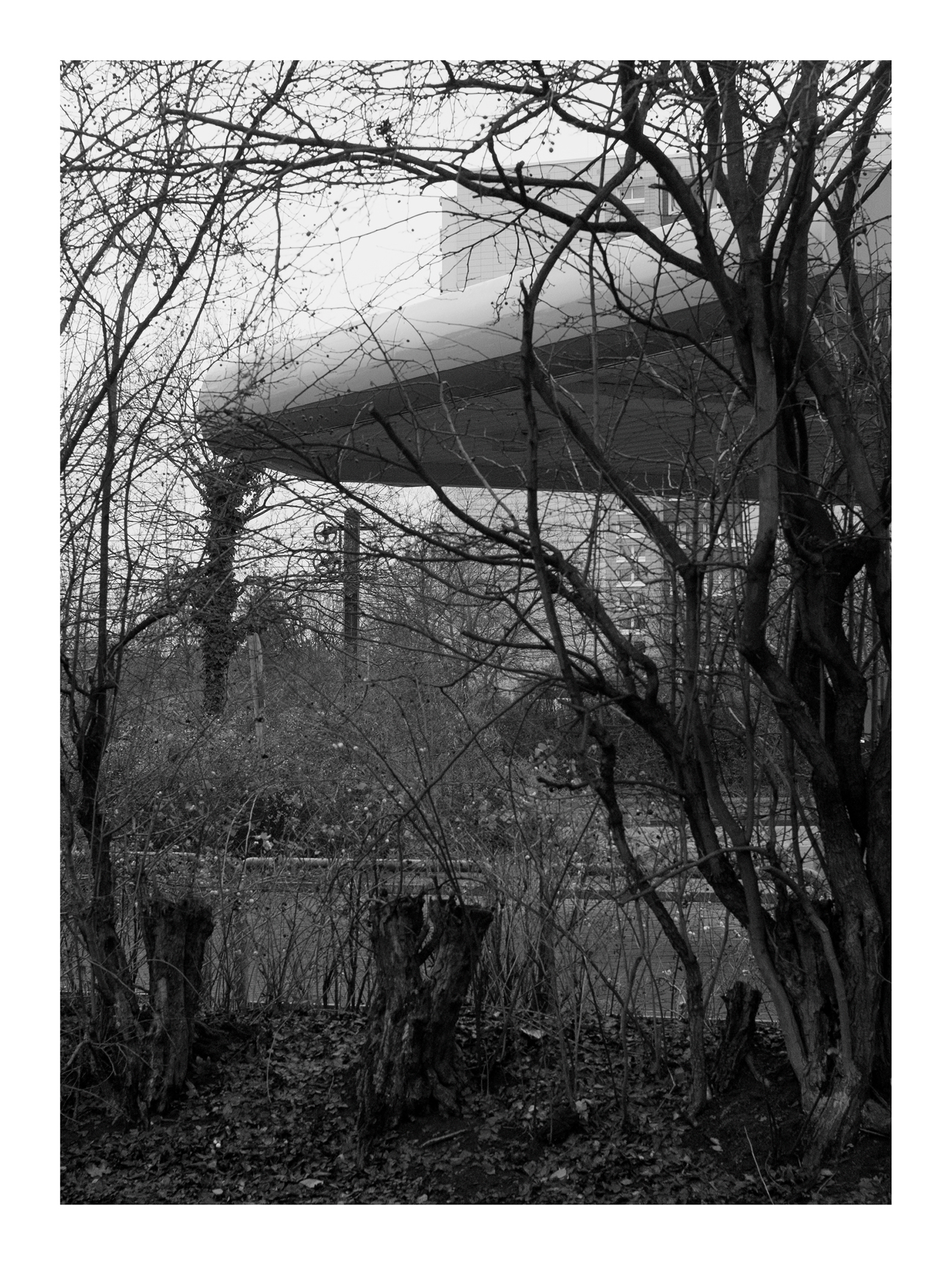

Between 2014 and 2018, photographer Michael Ashkin traveled frequently to Berlin to capture the city and its painful history. The result is the book 'Horizont', a book that shows Berlin as a grim city in fragmented compositions.

Tell us a little about your background?

My background is not straightforward. My parents were rational scientists and, perhaps in reaction to that, I tended to look for answers in what they considered irrelevant. In retrospect, I recognize that I have spent my life looking beside and past the objects I was told were important. I traveled on my own a lot when I was young, I studied Arabic in college and grad school, and then I worked on Wall Street for a few years. I found that experience so alienating that in my thirties I changed course and became an artist. Since then, I have photographed, made sculpture, painted, and fifteen years ago I found a job teaching at Cornell where I still work. Since 2014 I have mostly made photographs, but I still make sculpture and write a lot.

Can you tell us a bit more about your project Horizont?

When I first traveled to Berlin, I sensed that the outward form of the city expressed its painful history in a tangible but repressed way. Each block or building seemed to be trying lock its stories behind walls. Berlin feels like a city of barriers to looking and knowing, but the barriers themselves seemed to tell a consistent story. I began to make frequent trips there between 2014 and 2018. I would just walk, allowing myself to get lost, and photographing moments that revealed what I just described. It was a subjective experience, but as I worked, I noticed formal and combinatory patterns repeating in the photos. I felt that in this way the city was teaching me something, and I followed the formal queues to see where they would lead.

Can you tell us a bit more about your process for this project?

I shot without overthinking anything. I shot what I responded to. But when I returned home, I would look at the results carefully. As I often do, I shoot in landscape mode, but I set a cropping ratio for portrait, and this allows me to choose to slide a frame across the photo and choose a very precise image. In effect, this allows me to discover after the fact what it was I felt when I snapped the picture. Horizont as a book tries also to do something additional. As I lay out the photos for the book, I noticed that combinations of photographs achieved an uncanny effect that I liked. It was as if two photographs could produce a new place that told its own story, so each spread of that book is to me its own photograph.

What does photography mean to you?

Photography is a way of discovering a way behind the image your brain gives you by default. Our visual sense is programmed by a history determining what reality is or is not. In modern western culture, that reality has become remarkably one dimensional. Photography, by freezing vision, allows you to think about what you otherwise not have time to notice. Even with its technologically predetermined form, photography can give you a material analog of the world. It gives you details that language has not named. It shows you combinations of objects that ask questions not always easily answered. If, for example, you consider every object in a photograph equally important, then the questions a photograph can ask are almost infinite.

Tell us about your first camera

I first had an Instamatic, but early on my father gave me one of his two 35mm Voigtlanders from the 1940s. That is what inspired my love of the camera. It had collapsible bellows and no light meter, but I could still take pretty reasonable pictures even before I learned much about shutter speed and aperture.

Which other photographers, designers, artists or creative people are you loving at the moment?

That’s a hard question simply because there are so many artists and photographers that I love. But since I just opened it the other day, I will mention the wonderful and surprising book of photographs called Psychobuildings made by the artist Martin Kippenberger. Its images are low-res and casual, but they add up to create a funny but haunting shadow version of our truly absurd world.

© Pictures by

Michael Ashkin